MicMac Creation Story

This story has been passed down from generation to generation since time immemorial and it explains how Mik'Maq people came into existence in North America. The story tells about the relationship between the Great Spirit Creator and Human Beings and the Environment. It also explains a philosophical view of life which is indigenous to North America. This way of thinking is evident in the Native Languages and Cultures and in the spiritual practices.

The fact that the Mik'Maq people’s language, culture and spiritualism has survived for centuries is based on the creation story. Respect for their elders has given them wisdom about life and the world around them. The strength of their youth has given them the will to survive. The love and trust of their motherhood has given them a special understanding of everyday life.

Among the Mik'Maq people, the number seven is very meaningful. There are seven districts for distinct areas which encompasses an area of land stretching from the Gaspé coast of Quebec and includes New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. The most powerful spirit medicine is made from seven barks and roots. Seven men, representatives from each distinct area or Grand Council District sit inside a sweat-lodge smoke the pipe and burn the sweet grass. Inside the sweat-lodge, the Mik'Maqs will pour water over seven, fourteen and then twenty-one heated rocks to produce hot steam. A cleansing or purification takes place. A symbolic rebirth takes place and the men give thanks to the Spirit Creator, the Sun and the Earth. They also give thanks the first family, Glooscap, Nogami, Netaoansom, and Neganagonimgoosisgo. Listen to the story.

ONE

GISOOLG

Gisoolg is the Great Spirit Creator who is the one who made everything. The work Gisoolg in Mik'Maq means " you have been created ". It also means " the one credited for your existence".

The word does not imply gender. Gisoolg is not a He or a She, it is not important whether the Great Spirit is a He or a She.

The Mik'Maq people do not explain how the Great Spirit came into existence only that Gisoolg is responsible for everything being where it is today. Gisoolg made everything.

TWO

NISGAM

Nisgam is the sun which travels in a circle and owes its existence to isoolg. Nisgam is the giver of life. It is also a giver of light and heat.

The Mik'Maq people believe that Nisgam is responsible for the creation of the people on earth. Nisgam is Gisoolg’s helper. The power of Nisgam is held with much respect among the Mik'Maq and other aboriginal peoples. Nisgam owes its existence to Gisoolg the Great Spirit Creator.

THREE

OOTSITGAMOO

Ootsitgamoo is the earth or area of land upon which the Mik'Maq people walk and share its abundant resources with the animals and plants. In the Mik'Maq language Oetsgitpogooin means "the person or individual who stand upon this surface", or "the one who is given life upon this surface of land". Ootsitgamoo refers to the Mik'Maq world which encompasses all the area where the Mik'Maq people can travel or have travelled upon.

Ootsitgamoo was created by Gisoolg and was placed in the centre of the circular path of Nisgam, the sun. Nisgam was given the responsibility of watching over the Mik'Maq world or Ootsitgamoo. Nisgam shines bright light upon Oositgamoo as it passes around and this brought the days and nights.

FOUR

GLOOSCAP

After the Mik'Maq world was created and after the animals, birds and plants were placed on the surface, Gisoolg caused a bolt of lightening to hit the surface of Ootsitgamoo. This bolt of lightning caused the formation of an image of a human body shaped out of sand. It was Glooscap who was first shaped out of the basic element of the Mik'Maq world, sand.

Gisoolg unleashed another bolt of lightening which gave life to Glooscap but yet he could not move. He was stuck to the ground only to watch the world go by and Nisgam travel across the sky everyday. Glooscap watched the animals, the birds and the plants grow and pass around him. He asked Nisgam to give him freedom to move about the Mik'Maq world.

While Glooscap was still unable to move, he was lying on his back. His head was facing the direction of the rising sun, east, Oetjgoabaniag or Oetjibanoog. In Mik'Maq these words mean "where the sun comes up " and "where the summer weather comes from" respectively. His feet were in the direction of the setting sun or Oetgatsenoog. Other Mik'Maq words for the west are Oeloesenoog, "where the sun settles into a hallow" or Etgesnoog "where the cold winds come from". Glooscap’s right hand was pointed in the direction of the north or Oatnoog. His left hand was in the direction of the south or Opgoetasnoog. So it was the third big blast of lightening that caused Glooscap to become free and to be able to stand on the surface of the earth.

After Glooscap stood up on his feet, he turned around in a full circle seven times. He then looked toward the sky and gave thanks to Gisoolg for giving him life. He looked down to the earth or the ground and gave thanks to Ootsigamoo for offering its sand for Glooscap's creation. He looked within himself and gave thanks to Nisgam for giving him his soul and spirit.

Glooscap then gave thanks to the four directions east, north, west and south. In all he gave his heartfelt thanks to the seven directions.

Glooscap then travelled to the direction of the setting sun until he came to the ocean. He then went south until the land narrowed and he came to the ocean. He then went south until the land narrowed and he could see two oceans on either side. He again travelled back to where he started from and continued towards the north to the land of ice and snow. Later he came back to the east where he decided to stay. It is where he came into existence. He again watched the animals, the birds and the plants. He watched the water and the sky. Gisoolg taught him to watch and learn about the world. Glooscap watched but he could not disturb the world around him. He finally asked Gisoolg and Nisgam, what was the purpose of his existence. He was told that he would meet someone soon.

FIVE

NOGAMI

One day when Glooscap was travelling in the east he came upon a very old woman. Glooscap asked the old woman how she arrived to the Mik'Maq world. The old woman introduced herself as Nogami. She said to Glooscap, "I am your grandmother". Nogami said that she owes her existence to the rock, the dew and Nisgam, the Sun. She went on to explain that on one chilly morning a rock became covered with dew because it was sitting in a low valley. By midday when the sun was most powerful, the rock got warm and then hot. With the power of Nisgam, the sun, Gisoolg's helper, the rock was given a body of an old woman. This old woman was Nogami, Glooscap's grandmother.

Nogami told Glooscap that she come to the Mik'Maq world as an old woman, already very wise and knowledgeable. She further explained that Glooscap would gain spiritual strength by listening to and having great respect for his grandmother. Glooscap was so glad for his grandmother's arrival to the Mik'Maq world he called upon Abistanooj, a marten swimming in the river, to come ashore. Abistanooj did what Glooscap had asked him to do. Abistanooj came to the shore where Glooscap and Nogami were standing. Glooscap asked Abistanooj to give up his life so that he and his grandmother could live. Abistanooj agreed. Nogami then took Abistanooj and quickly snapped his neck. She placed him on the ground. Glooscap for the first time asked Gisoolg to use his power to give life back to Abistanooj because he did not want to be in disfavour with the animals.

Because of marten's sacrifice, Glooscap referred to all the animals as his brothers and sisters from that point on. Nogami added that the animals will always be in the world to provide food, clothing, tools, and shelter. Abistanooj went back to the river and in his place lay another marten. Glooscap and Abistanooj will become friends and brothers forever.

Nogami cleaned the animal to get it ready for eating. She gathered the still hot sparks for the lightening which hit the ground when Glooscap was given life. She placed dry wood over the coals to make a fire. This fire became the Great Spirit Fire and later go to be known as the Great Council Fire.

The first feast of meat was cooked over the Great Fire, or Ekjibuctou. Glooscap relied on his grandmother for her survival, her knowledge and her wisdom. Since Nogami was old and wise, Glooscap learned to respect her for her knowledge. They learned to respect each other for their continued interdependence and continued existence.

SIX

NETAOANSOM

One day when Glooscap and Nogami were walking along in the woods, they came upon a young man. This young man looked very strong because he was tall and physically big. He had grey coloured eyes. Glooscap asked the young man his name and how he arrived to the Mik'Maq world. The young man introduced himself. He told Glooscap that his name is Netaoansom and that he is Glooscap's sister's son. In other words, his nephew. He told Glooscap that he is physically strong and that they could all live comfortably. Netaoansom could run after moose, deer and caribou and bring them down with his bare hands. He was so strong. Netaoansom said that while the east wind was blowing so hard it caused the waters of the ocean to become rough and foamy. This foam got blown to the shore on the sandy beach and finally rested on the tall grass. This tall grass is sweetgrass. Its fragrance was sweet. The sweetgrass held onto the foam until Nisgam, the Sun, was high in the midday sky. Nisgam gave Netaoansom spiritual and physical strength in a human body. Gisoolg told Glooscap that if he relied on the strength and power of his nephew he would gain strength and understanding of the world around him.

Glooscap was so glad for his nephew's arrival to the Mik'Maq world, he called upon the salmon of the rivers and seas to come to shore and give up their lives. The reason for this is that Glooscap, Netoansom and Nogami did not want to kill all the animals for their survival. So in celebration of his nephew's arrival, they all had a feast of fish. They all gave thanks for their existence. They continued to rely on their brothers and sisters of the woods and waters. They relied on each other for their survival.

SEVEN

NEGANOGONIMGOSSEESGO

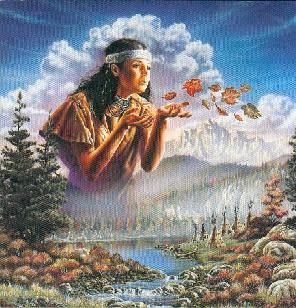

While Glooscap was sitting near a fire, Nogam was making clothing out of animal hides and Netaoansom was in the woods getting food. A woman came to the fire and sat beside Glooscap. She put her arms around Glooscap and asked "Are you cold my son?" Glooscap was surprised he stood up and asked the woman who she is and where did she come from. She explained that she was Glooscap's mother. Her name is Neganogonimgooseesgo. Glooscap waited until his grandmother and nephew returned to the fire then he asked his mother to explain how she arrived to the Mik'Maq world.

Neganogonimgooseesgo said that she was a leaf on a tree which fell to the ground. Morning dew formed on the leaf and glistened while the sun, Nisgam, began its journey towards the midday sky. It was at midday when Nisgam gave life and a human form to Glooscap's mother. The spirit and strength of Nisgam entered into Glooscap's mother.

Glooscap's mother said that she brings all the colours of the world to her children. She also brings strength and understanding. Strength to withstand earth's natural forces and understanding of the Mik'Maq world; its animals and her children, the Mik'Maq. She told them that they will need understanding and co-operation so they all can live in peace with one another.

Glooscap was so happy that his mother came into the world and since she came from a leaf, he called upon his nephew to gather nuts, fruits of the plants while Nogami prepared a feast. Glooscap gave thanks to Gisoolg, Nisgam, Ootsitgamoo, Nogami, Netaoansom and Neganogonimgooseesgo. They all had a feast in honour of Glooscap's mother’s arrival to the world of Mik'Maqs.

The story goes on to say that Glooscap, the man created from the sand of the earth, continued to live with his family for a very long time. He gained spiritual strength by having respect for each member of the family. He listened to his grandmother' s wisdom. He relied on his nephew' s strength and spiritual power. His mother' s love and understanding gave him dignity and respect. Glooscap' s brothers and sisters of the wood and waters gave him the will and the food to survive. Glooscap now learned that mutual respect of his family and the world around him was a key ingredient for basic survival. Glooscap's task was to pass this knowledge to his fellow Mik'Maq people so that they too could survive in the Mik'Maq world. This is why Glooscap became a central figure in Mik'Maq story telling.

One day when Glooscap was talking to Nogami he told her that soon they would leave his mother and nephew. He told her that they should prepare for that occasion. Nogami began to get all the necessary things ready for a long journey to the North. When everyone was sitting around the Great Fire one evening, Glooscap told his mother and nephew that he and Nogami are going to leave the Mik'Maq world. He said that they will travel in the direction of the North only to return if the Mik'Maq people were in danger. Glooscap told his mother and nephew to look after the Great Fire and never to let it go out.

After the passing of seven winters, "elwigneg daasiboongeg", seven sparks will fly from the fire and when they land on the ground seven people will come to life. Seven more sparks will land on the ground and seven more people will come into existence. From these sparks will form seven women and seven men. They will form seven families. These seven families will disperse into seven different directions from the area of the Great Fire. Glooscap said that once the seven families their place of destination, they will further divide into seven groups.

Each group will have their own area for their subsistence so they would not disturb the other groups. He instructed his mother that the smaller groups would share the earth's abundance of resources which included animals, plants and fellow humans.

Glooscap told his mother that after the passing of seven winters, each of the seven groups would return to the place of the Great Fire. At the place of the fire all the people will dance, sing and drum in celebration of their continued existence in the Mik'Maq world. Glooscap continued by saying that the Great Fire signified the power of the Great Spirit Creator, Gisoolg. It also signified the power and strength of the light and heat of Nisgam, the sun. The Great Fire held the strength of Ootsitgamoo the earth. Finally the fire represented the bolt of lightening which hit the earth from which Glooscap was created. The fire is very sacred to the Mik'Maqs. It is the most powerful spirit on earth.

Glooscap told his mother and nephew that it is important for the Mik'Maq to give honour, respect and thanks to the seven spiritual elements. The fire signifies the first four stages of creation, Gisoolg, Nisgam, Oositgamoo and Glooscap. Fire plays a significant role in the last three stages as it represents the power of the sun, Nisgam.

In honour of Nogamits arrival to the Mik'Maq world, Glooscap instructed his mother that seven, fourteen and twenty-one rocks would have to be heated over the Great Fire. These heated rocks will be placed inside a wigwam covered with hides of moose and caribou or with mud. The door must face the direction of the rising sun. There should be room from seven men to sit comfortably around a pit dug In the centre where up to twenty-one rocks could be placed. Seven alders, seven wild willows and seven beech saplings will be used to make the frame of the lodge. This lodge should be covered with the hides of moose, caribou, deer or mud.

Seven men representing the seven original families will enter into the lodge. They will give thanks and honour to the seven directions, the seven stages of creation and to continue to live in good health. The men will pour water over the rocks causing steam to rise in the lodge to become very hot. The men will begin to sweat up to point that it will become almost unbearable. Only those who believe in the spiritual strength will be able to withstand the heat. Then they will all come out of the lodge full of steam and shining like new born babies. This is the way they will clean their spirits and should honour Nogami's arrival.

In preparation of the sweat, the seven men will not eat any food for seven days. They will only drink the water of golden roots and bees nectar. Before entering the sweat the seven men will burn the sweetgrass. They will honour the seven directions and the seven stages of creation but mostly for Netawansom's arrival to the Mik'Maq world. The sweet grass must be lit from the Great Fire.

Glooscap's mother came into the world from the leaf of a tree, so in honour of her arrival tobacco made from bark and leaves will be smoked. The tobacco will be smoked in pipe made from a branch of a tree and a bowl made from stone.

The pipe will be lit from sweetgrass which was lit from the Great Fire. The tobacco made from bark, leaves and sweetgrass represents Glooscap's grandmother, nephew and mother. The tobacco called "spebaggan" will be smoked and the smoke will be blown in seven directions.

After honouring Nogami's arrival the Mik'Maq shall have a feast or meal. In honour of Netawansom they will eat fish. The fruits and roots of the trees and plants will be eaten to honour Glooscap's mother.

Glooscap's final instruction to his mother told her how to collect and prepare medicine from the barks and roots of seven different kinds of plant. The seven plants together make what is called "ektjimpisun". It will cure mostly every kind of illness in the Mik'Maq world. The ingredients of this medicine are: "wikpe"(alum willow), "waqwonuminokse"(wild black-cherry), "Kastuk"(ground hemlock), and "kowotmonokse"(red spruce).

The Mik'Maq people are divided into seven distinct areas which are as follows:

1.Gespegiag 2.Sigenitog 3.Epeggoitg a, Pigtog 4.Gespogoitg 5.Segepenegatig 6.Esgigiag 7.Onamagig

Return to Menu